Author: David Santiuste; Pen and Sword Military: ISBN 978 184884 5497. This softback edition has 146 pages with a further 45 of abbreviations, notes and bibliography.

This is not a full biography of Edward IV. It is more a reassessment of his military career and role as a commander. By the author’s own admission, it is not based on extensive archival research of his own. The notes, however, suggest reliance on some of the most prominent experts of the period, notably the late Professor Charles Ross, in conjunction with more contemporary research. Helpfully, it does include a family tree, which is necessary because of the complex family connections of most of the main players; the importance of which cannot be underestimated. Having looked up David Santiuste (a tutor at Edinburgh University) on the internet, it is clear to me that although this work is constructed in a solidly academic style, he intended this book to also appeal to a more general readership.

This is not a full biography of Edward IV. It is more a reassessment of his military career and role as a commander. By the author’s own admission, it is not based on extensive archival research of his own. The notes, however, suggest reliance on some of the most prominent experts of the period, notably the late Professor Charles Ross, in conjunction with more contemporary research. Helpfully, it does include a family tree, which is necessary because of the complex family connections of most of the main players; the importance of which cannot be underestimated. Having looked up David Santiuste (a tutor at Edinburgh University) on the internet, it is clear to me that although this work is constructed in a solidly academic style, he intended this book to also appeal to a more general readership.

To modern thinking, most of the battles in the Wars of the Roses would only be classified as skirmishes. It must, however be remembered that the population of the country at this time was in the region of 2,500,000 and therefore the pool of men to fight was limited, especially as this was effectively civil war and the combatants split between the two sides.

David Santiuste suggests that events at the Battle of Northampton (1460) which was Edward’s first command in the absence of his father, may have influenced his later strategic conduct; although it is likely that Warwick had overall command.

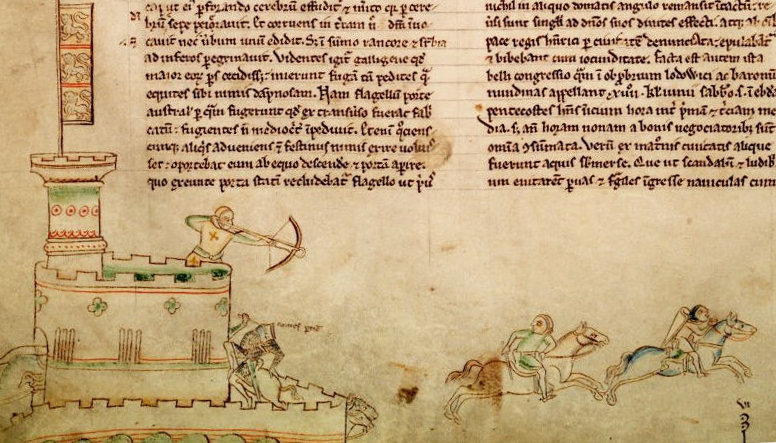

The author asserts that Edward’s leadership qualities stem from his great height and personal charisma, even as an 18 year old. The battle of Mortimer’s Cross (1461) was Edward’s first personally crucial battle and like many more, the outcome was heavily influenced by the weather. The rare phenomenon of parhelia (the apparition of three suns caused by refraction of sunlight through ice crystals) was seen before the battle and Edward convinced his frightened men that this was a good omen, representing the Holy Trinity. Surely quick thinking on his part, as this would have bolstered the morale of a frightened body of men. People in the Middle Ages were very superstitious and believed strongly in omens of this sort. The fact is that Edward’s great height of some 6ft 4” must have made him very noticeable. To men seeing him in the thick of the fighting would have been a great encouragement. Mr Santiuste quotes from the leading commentators of the time and even Edward’s detractors all admit to his fine stature and good looks. No bad thing for a medieval king who had to take the crown in battle and then demonstrate strength enough to rule.

The author asserts that Edward’s leadership qualities stem from his great height and personal charisma, even as an 18 year old. The battle of Mortimer’s Cross (1461) was Edward’s first personally crucial battle and like many more, the outcome was heavily influenced by the weather. The rare phenomenon of parhelia (the apparition of three suns caused by refraction of sunlight through ice crystals) was seen before the battle and Edward convinced his frightened men that this was a good omen, representing the Holy Trinity. Surely quick thinking on his part, as this would have bolstered the morale of a frightened body of men. People in the Middle Ages were very superstitious and believed strongly in omens of this sort. The fact is that Edward’s great height of some 6ft 4” must have made him very noticeable. To men seeing him in the thick of the fighting would have been a great encouragement. Mr Santiuste quotes from the leading commentators of the time and even Edward’s detractors all admit to his fine stature and good looks. No bad thing for a medieval king who had to take the crown in battle and then demonstrate strength enough to rule.

Edward was not present at the second battle of St Albans, which followed hard on his victory at Mortimer’s Cross. Warwick was comprehensively defeated at this encounter and I think it true to say that he may have been a better sailor than a soldier. The author suggests that Edward was already seeing that his destiny lay in his own hands and he already ‘no longer bowed to Warwick’.

Edward was not present at the second battle of St Albans, which followed hard on his victory at Mortimer’s Cross. Warwick was comprehensively defeated at this encounter and I think it true to say that he may have been a better sailor than a soldier. The author suggests that Edward was already seeing that his destiny lay in his own hands and he already ‘no longer bowed to Warwick’.

In spite of this defeat, the Yorkists gained control of London because the city denied access to the Lancastrians. This has much to do with the fact that the Lancastrian armies of the period developed a reputation for plunder and savagery towards the general populace. Edward, on the other hand, was noted for his strict discipline, commanding ‘that no man in his own army should act thus, on pain of death’. Then came probably the most important battle of this first part of the civil war and bloodiest ever fought on English soil; Towton.

In spite of this defeat, the Yorkists gained control of London because the city denied access to the Lancastrians. This has much to do with the fact that the Lancastrian armies of the period developed a reputation for plunder and savagery towards the general populace. Edward, on the other hand, was noted for his strict discipline, commanding ‘that no man in his own army should act thus, on pain of death’. Then came probably the most important battle of this first part of the civil war and bloodiest ever fought on English soil; Towton.

This represented a decisive Yorkist victory, which resulted in Edward’s confirmation as king, followed by his coronation. The butcher’s bill of Towton has been the subject of much speculation for many years and is inevitably discussed in this work, with the author attempting to rationalise the claims of the chroniclers of the period with the more recent archaeological evidence, concluding that whatever the final figures were, the armies of both sides would have been as large as possible (bearing in mind the losses suffered in recent battles) because the outcome of this battle would confirm the crown on Edward or Henry.

This represented a decisive Yorkist victory, which resulted in Edward’s confirmation as king, followed by his coronation. The butcher’s bill of Towton has been the subject of much speculation for many years and is inevitably discussed in this work, with the author attempting to rationalise the claims of the chroniclers of the period with the more recent archaeological evidence, concluding that whatever the final figures were, the armies of both sides would have been as large as possible (bearing in mind the losses suffered in recent battles) because the outcome of this battle would confirm the crown on Edward or Henry.

This book does not deal with the personal, more salacious side of Edward’s character. Although the issue of Edward’s marriage is briefly mentioned, the author develops the many reasons for Warwick’s disaffection with Edward’s regime. It is too easy to simply blame the marriage. Edward was clearly a very able sovereign and in fact, his choice of bride was the final realisation to the Earl of Warwick that Edward was his own man and wasn’t going to be ‘guided’ by the earl on all main issues. I think it likely that the breach with Warwick was inevitable as he probably believed he would be the power behind the throne – no matter who the king married.

The author then goes on to describe the events resulting in the final disintegration of their relationship, which ultimately resulted in the alliance of Edward’s treacherous brother George with the earl and his tactical withdrawal to the Low Countries to regroup. Had the king not done this, it would have surely resulted in the loss of his head, never mind what turned out to be the temporary loss of his throne.

Mr Santiuste details Edward’s time in Bruges and eventual persuasion of his brother-in-law, Charles the Bold to lend him the resources to mount an invasion to regain his crown. Edward landed at Ravenspur at the mouth of the Humber on March 2nd 1471, cleverly suggesting that he had only come to claim his rights as the Duke of York, but quickly gathered an army and with remarkable speed regained London; the Lancastrian lords abandoning Henry VI to his fate.

Edward’s supporters had soon rallied and rearmed and the Yorkists were able to give battle at Barnet on April 14th, Easter Sunday 1471. A remarkable turn around, which resulted in the death of the Earl of Warwick, finally breaking Neville power. George of Clarence had turned his coat again and now Edward went on to fight his final battle at Tewkesbury, resulting in the death of Henry VI’s heir and most of the Lancastrian hierarchy. Those that survived went into exile. Only then did he order the death of Henry VI, probably belatedly realising that while ever he lived, he would be a focus for rebellion.

Edward’s supporters had soon rallied and rearmed and the Yorkists were able to give battle at Barnet on April 14th, Easter Sunday 1471. A remarkable turn around, which resulted in the death of the Earl of Warwick, finally breaking Neville power. George of Clarence had turned his coat again and now Edward went on to fight his final battle at Tewkesbury, resulting in the death of Henry VI’s heir and most of the Lancastrian hierarchy. Those that survived went into exile. Only then did he order the death of Henry VI, probably belatedly realising that while ever he lived, he would be a focus for rebellion.

The second period of Edward’s reign was marked by peace as there was now no viable threat to his regime. Probably the most controversial event was the Treaty of Picquigny (1475). Edward took an army to France, but agreed the treaty with Louis XI on the bridge at Picquigny, which paid a pension to Edward of 50,000 crowns per annum with a down payment of 75,000. This continued for seven years, until Louis reneged on the agreement. This represents millions at today’s values and Edward probably regarded it as his finest hour, thereby avoiding a costly war and supplementing the exchequer. His remaining brother, Richard however, did not. This event may mark the beginnings of his disaffection with the king, while remaining a loyal lieutenant.

The second period of Edward’s reign was marked by peace as there was now no viable threat to his regime. Probably the most controversial event was the Treaty of Picquigny (1475). Edward took an army to France, but agreed the treaty with Louis XI on the bridge at Picquigny, which paid a pension to Edward of 50,000 crowns per annum with a down payment of 75,000. This continued for seven years, until Louis reneged on the agreement. This represents millions at today’s values and Edward probably regarded it as his finest hour, thereby avoiding a costly war and supplementing the exchequer. His remaining brother, Richard however, did not. This event may mark the beginnings of his disaffection with the king, while remaining a loyal lieutenant.

Edward IV is a much ignored king who school history books write off as a tyrannical despot. Yet this is surely not so. David Santiuste describes a man who time and again tried to rehabilitate his enemies, with varying success. His patience with the treachery of his brother George is a good example of this. History has shown that he was the victor of this conflict and an undefeated general. When Edward died unexpectedly in 1483, he was personally rich and the exchequer was full.

The four battles of Mortimer’s Cross, Towton, Barnet and Tewkesbury are among the most important to English history. This book gives full accounts of them all, with details of weapons, tactics and the logistical difficulties that a medieval army would face. The book also includes three maps; one a general map showing the locations of all the battles and two more detailed ones, covering Towton and Tewkesbury. I would have liked to see two more to cover Mortimer’s Cross and Barnet and find myself wondering why these weren’t included.

The four battles of Mortimer’s Cross, Towton, Barnet and Tewkesbury are among the most important to English history. This book gives full accounts of them all, with details of weapons, tactics and the logistical difficulties that a medieval army would face. The book also includes three maps; one a general map showing the locations of all the battles and two more detailed ones, covering Towton and Tewkesbury. I would have liked to see two more to cover Mortimer’s Cross and Barnet and find myself wondering why these weren’t included.

Recently Professor Saul David has described Edward IV as one of history’s most ‘overrated’ people. David Santiuste’s work demonstrates that Edward’s record as a commander and leader of men equals the more accepted warrior princes of the Hundred Years War.

This is a comparatively short work, but the author has been careful not to be distracted from his main theme, while placing Edward’s actions in the context of his policies, both at home and in a wider Europe. A worthwhile read.